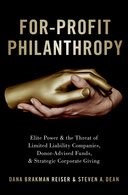

For-Profit Philanthropy: Elite Power and the Threat of Limited Liability Companies, Donor-Advised Funds, and Strategic Corporate Giving

Philanthropy is broken. And there is no easy fix.

In a nutshell, that is the overriding message that emerges from For-Profit Philanthropy: Elite Power and the Threat of Limited Liability Companies, Donor-Advised Funds, and Strategic Corporate Giving by Dana Brakman Reiser, the Centennial Professor of Law at Brooklyn Law School, and Steven A. Dean, a professor of law and co-director of the law school’s Center for the Study of International Business Law.

What broke philanthropy, and can it be fixed? Brakman Reiser and Dean begin with a detailed examination of the rise of for-profit LLCs, commercially affiliated donor-advised funds (DAFs) such as Fidelity Charitable and Vanguard Charitable, and strategic corporate philanthropy programs. But that examination also includes background on the history of private foundations. Younger readers may be surprised to learn that, while philanthropic giving existed long before the term became commonplace, the legal structure of private foundations is relatively new and came about after years of evaluation, debate, and negotiation.

The 1969 Tax Reform Act enabled wealthy individuals to establish private foundations with a significant amount of freedom and the possibility of perpetuity—in return for governmental regulation and transparency. The law constructed a (lightly) regulated private foundation form that allowed the wealthy to “credibly commit to using a share of their vast resources to serve public ends rather than private ones.” It essentially separated private foundations from public charities. Public charities are built by the people who donate to them; private foundations are funded by wealthy individuals without a “public constituency,” which Congress saw as inherently undemocratic.

Brakman Reiser and Dean could have included more about the personalities and debates behind the creation of one of the most significant political successes of the past century, which they describe as the “Grand Bargain.” But if the authors’ predictions about the future of philanthropy come to pass, private foundations as we know them will already have been condemned to the dustbins of history.

[I]f the authors’ predictions about the future of philanthropy come to pass, private foundations as we know them will already have been condemned to the dustbins of history.

While Brackman Reiser and Dean occasionally fall into recitations of legal structure, more often than not, they describe the future of philanthropy like those who write about climate change: fatalistically. Indeed, readers are left fearing that their message may well seem as inevitable as rising global temperatures.

What has been lost in this crisis? Trust.

“Improbably,” they write, “federal tax laws constraining the targeting, timing, and transparency of philanthropy have preserved the public’s trust in wealthy donors for more than fifty years. Increasingly, for-profit philanthropy allows individual and corporate donors to sidestep such requirements when it suits them. Undermining this regime risks a catastrophic loss of public trust in the value of private philanthropic endeavors. For-profit philanthropy threatens the very idea of philanthropy as a public good distinct from private gain.”

The Grand Bargain started to unravel with the legalization of commercially affiliated DAFs and philanthropy LLCs. For example, as an LLC, an organization like the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative or Omidyar Network could decide to use its resources for a wide range of issues, including political activities that private foundation are precluded from engaging in. “By turning its back on the Grand Bargain, for-profit philanthropy curtails public oversight,” they write. “In truth, even wealthy funders may not know whether a philanthropy LLC will remain committed to a cause.”

So how can philanthropy as we know it be saved?

[A]s an LLC, an organization like the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative or Omidyar Network could decide to use its resources for a wide range of issues, including political activities that private foundation are precluded from engaging in.

The book’s final three chapters provide possibilities to bring for-profit philanthropists back between the guardrails that were established in 1969. For example, regulatory changes might include requiring DAFs “to clearly and publicly name recipients of dormant assets, carefully easing strictures targeted at ‘self-dealing’ by foundations, and making benefit reports mainstream” to help restore trust between the public and the wealthy. “On their own,” the authors write, “none of these narrow proposals would rebuild the trust between elites and the public the Grand Bargain once provided....[But] targeted measures could allow the public to ensure that for-profit philanthropy addresses urgent problems of today, rather than merely burnishing the images of the wealthiest Americans.”

The incremental approach the authors propose includes reexamining the old questions surrounding the Grand Bargain and giving it a makeover that could help address equity issues. But it could also constitute pushing a boulder halfway up a hill. While the authors don’t explicitly express such cynicism, the U.S. political environment is as volatile as ever, and major tax reform seems unlikely in the current Congress. So perhaps the for-profit philanthropists would respond to the authors’ second idea: Ask wealthy elites to act strategically to reinforce that trust.

“A precisely tailored corporate governance scheme could impose targeting limitations on strategic corporate philanthropy conducted through a dedicated subsidiary,” the authors suggest. With their resources and the fear of public humiliation, they argue, elites could turn to private ordering, where they agree to regulate themselves. “For those with the means, designing a way to shield for-profit philanthropy’s nimble new paradigm against a backlash powered by distrust and that threatens to prompt potentially intrusive regulation could prove a prudent investment.”

The third option the authors put forward involves three additional visions for change to create what they call “a more perfect bargain.” It likely would start with a wealth tax—collecting taxes on wealth rather than simply income—and progress to overhauling election and campaign spending laws “to reduce elite influence and enhance participation by marginalized communities.” Depending on how well such legislation were crafted, “[a] more perfect bargain” could benefit both the wealthy and the rest of us by preserving a balance between assets.

A “more perfect bargain”...likely would start with a wealth tax—collecting taxes on wealth rather than simply income—and progress to overhauling election and campaign spending laws “to reduce elite influence and enhance participation by marginalized communities.”

Again, given the current political environment, such legislation seems unlikely to be raised in the current Congress. The authors seem to recognize the challenge, even if they appear to advocate for their third option.

“Private ordering may not be a Wizard of Oz, with the power to grant courage to corporations, a heart to commercially affiliated donor-advised funds, and a brain to philanthropy LLCs. But like the lion, the tin man, and the scarecrow, each may find that they have no need for magic. Carefully designed self-regulatory commitments could reveal each to be precisely what it aspires to become.”

Of course, legislative inertia is also a distinct possibility, which would leave the sector on an already slippery slope. As such, more philanthropy LLCs would be formed by wealthy elites, more check-book philanthropy would be holding onto charitable assets in commercially affiliated DAFs, and strategic corporate philanthropy would continue beyond the regulatory framework, leaving the corporations to determine for themselves whether their giving serves the public.

Only hope remained in Pandora’s box after its lid was opened and all manner of evil and misery were loosed upon the Earth. Whether those donors can rebuild the trust that for-profit philanthropic tools have helped dismantle remains to be seen. In the meantime, Brakman Reiser and Dean have produced a book that is sure to be reexamined again and again as the U.S. economy emerges from the throes of the COVID-19 pandemic and spawns even wealthier philanthropic elites who choose to innovate the innovations.

Matt Sinclair is editor of Philanthropy News Digest.