Funders have the wrong idea about democracy and Indian Country

We know the drill in Indian Country by now. Election year looms close on the horizon and Native community groups and Tribes doing the critical work of governing and responding to community needs are offered a last-minute influx of funding for voter engagement. Rinse and repeat until the next big election.

And while no organization or Tribe will say no to the dollars that support Indian Country voter engagement, funders have the wrong idea. As Indigenous people, we prioritize building lasting and meaningful relationships. Our relationships within our communities, the natural world, our culture, and yes, even democracy, are grounded in reciprocity and deep commitment to community engagement. We believe in building enduring relationships and earning the trust of our Native relatives.

For philanthropy to be effective in Indian Country, it must go beyond simply focusing on the short-term benefits of voter turnout during an election year, and instead prioritize ongoing long-term funding commitments to 501(c)(3) and (c)(4) organizations. To build movements, we must harness the power of our values for effective voter engagement and advocacy. Our belief systems are the source of our collective power. Ancestral knowledge illuminates the connection between the past and the future. Native community organizing is guided by how we walk, organize, and show up in the present. And those elements should guide how funders invest in Indian Country.

Native Organizers Alliance (NOA) strives to facilitate collaboration between grassroots community members and Tribal and traditional leadership, as well as between urban and reservation communities. We work through our networks to build long-lasting partnerships. We strive to make sure all sectors of Tribal and Native communities are heard.

The 2020 election saw record-breaking numbers of Native voters. NOA’s work was part of grassroots efforts to bring about this historic turnout. Results reflected the impact of more than 100 pairs of moccasins on the ground in five critical swing states, working full-time in their own communities—aunties and grandmothers reaching out to their younger and older Native relatives through the traditional “moccasin path.” This community-centered connection to one another and to a shared culture was the key to success. Trust was built through ongoing engagement. More Native voters turned out than ever before because the moccasins on the ground were trusted people in their community—someone they knew and trusted, often from families who have known one another for generations.

In one case, a Native women’s domestic violence shelter was so invested in ensuring that everyone had a voice in the election, they helped women seeking their services register to vote as a part of the intake process. A pilot program has begun to allow five Indian Health Service facilities to do the same. But there was a problem: Once the shelter registered voters, they didn’t have the capacity or resources to mobilize those potential voters or organize a civic engagement plan. They couldn’t provide candidate education or compile voter guides or scorecards. To advocate effectively for policy changes, 501(c)(3) and (c)(4) organizations need funds for the continuous engagement necessary to establish trust and support lifetime civic engagement.

A grassroots movement is growing in Indian Country aimed at building Native political power. It is not funded by electoral cycles. It is a natural outgrowth of advocacy and spreading awareness of how important it is to have Native representation and allies in public office who understand Indian Country. What we need is an ongoing commitment by philanthropy to engage in creating a multiracial democracy in which voter turnout is not an end in itself, but one tool in the toolbox to influence policy.

Voter engagement and advocacy between elections builds momentum for movements to drive profound system changes in the long term. Tribes and Native community groups need the resources to weave together an organizing strategy with a narrative and a cultural approach to deepen our communities’ understanding of the power of our values and its connection to voting and advocacy. It takes time.

In the wake of the 2020 election, we saw how Indian Country turned out do the hard work of defending our sovereignty on the issues of climate, protection of sacred places, and voting rights for all.

Alongside other Native organizations, NOA launched a national campaign to encourage Congress to confirm the appointment of the first Native woman to a cabinet position. The confirmation of Deb Haaland as secretary of the interior was a monumental victory for Native representation in government. Finally, after centuries, we, Native people have a seat at this table that we never had before. And we’re not going back.

Organizers and Tribal nations also pressed the Biden administration to undo the damage of the prior administration, to reinstate vital environmental protections that threaten our sacred Indigenous places. In 2021, the Red Road to DC Totem Journey united Native community organizers, organizations, and Tribal nations to send a message to President Joe Biden: The failure of government to respect free, prior, and informed consent led to the desecration and destruction of sacred places. As long as the federal government allows development and fossil fuel extraction projects without the permission of Tribes, the places Native peoples gather traditional foods, hold ceremonies, and pray are at risk. The health and well-being of our land and water is under duress due to climate change.

Months later, Biden signed an executive order directing federal agencies to strengthen treaty protections and develop plans to engage Tribes. It’s a strategy that has resulted in over 60 Tribal-federal co-management projects.

This is the kind of engagement that philanthropy overlooks when it focuses all its energy on election cycles. Organizing in Indian Country is grounded in our ancestral practices of ongoing community engagement. Building infrastructure for Native advocacy and power over multiple years requires it.

Organizing in Indian Country can deepen understanding in our Native communities about how the political system works, or when it doesn’t, and how it can be part of solving problems. But Tribes and Native organizations doing the work on the ground need the capacity and resources to consistently engage in this kind of deep policy work and civic engagement.

Philanthropy has a critical role to play in defending a multiracial democracy. Organizations building grassroots political power need funding for their operations beyond just an election cycle. Lasting and ongoing investments are needed to support our distinctly Native brand of values-driven organizing that moves minds, hearts, souls, and moccasins, to protect and expand democracy for all.

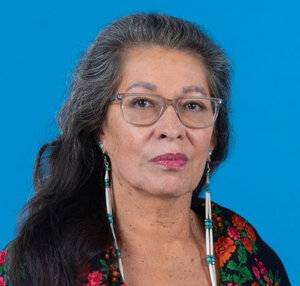

Judith Le Blanc (Caddo) is executive director of Native Organizers Alliance.