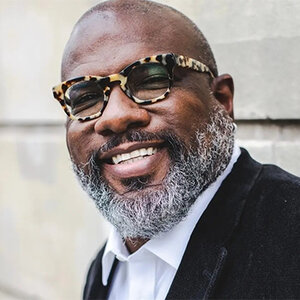

James C. Horton, President, Harlem School of the Arts: Investing in the arts is investing in humanity

April 27, 2023

James C. Horton was appointed president of Harlem School of the Arts (HSA) in the fall of 2022. Prior to joining HSA, he was vice president of education and engagement at the Museum of the City of New York. Horton is the seventh president of HSA, which will celebrates its 60th anniversary in the coming year.

Horton studied theater and communications at Southern University in Baton Rouge and participated in the Shannon Leadership Institute in St. Paul, Minnesota, and the Columbia University Business School Institute for Not-for-Profit Management.

Philanthropy News Digest asked Horton about leading the organization as it reemerges from the pandemic, bringing back its in-person gala this year as well as traditional in-person classes, and implementing new programs, the intersection of social justice and arts funding, and what the next school year has in store for students.

Philanthropy News Digest: What challenges did you face in taking the reins of the school as it was emerging from the pandemic, transitioning from virtual programing back to more in-person programing?

James C. Horton: I think one of the biggest challenges between the transition from virtual back to real life was that we didn’t quite know what to expect. We thought that through the success of our summer camp last summer, we would have a full student body back [and] it would look similar to what it did in 2019, but it didn’t. It really let us know two major things: One, maybe our community isn’t quite ready to come back and do the exact same things that they used to do in person, given this new virtual world—it was always there, but we really leaned into it at the height of the pandemic when we couldn’t physically be together. And two, how do we keep some of that virtual work going? That is a different level of infrastructure that we would need to put in place to support. I think that as we start to program and think toward the future, there’s an opportunity to strike a balance with real-life programming for our immediate community: How do we continue to connect in this virtual environment and not cannibalize our in-person offerings?

The thing that probably translated the easiest and most efficiently was our media design programming. Given the very nature of it being virtual, you can do a lot on your own. Even when you’re in person, some of that instruction takes place on the computer screen.

Some of our younger kids started school in a virtual environment, so they don’t know what it’s like to be physically in person in an education environment. Those are two and a half years that they would have gotten practice being in a classroom. They’re learning that now and they’re five years old. So that’s been different. And then also thinking about the power of the arts as it pertains to processing social-emotional learning and the trauma that we’ve all endured over the past few years and continue to endure—civil unrest on a global scale. The things that are happening have not stopped. Folks are still receiving unjust treatment in society by those who are supposed to be protecting them. Things are still inequitable and access is still a big issue in underserved communities, and our kids are a little bit more comfortable talking about those things.

PND: What does social justice look like at HSA? What role does arts education play in advancing social justice?

JCH: Dorothy Maynor created this school in 1964 in the basement of a church right down the block and then raised $2 million to have a 37,000-square-foot school built in 1977. She opened it up to the community to engage in art-centered learning. That, to me, is one of the greatest acts of social justice that you will ever see: Creating a space and holding a place for people to experience joy and creativity and challenge their thinking. As we think about what that means today—providing opportunities for our young people to have those conversations—I think of social justice as not an end to a means but a conversation starter and a way to perceive and navigate the world. A lot of what we talk about is not necessarily social justice as much as it is what is the social impact of our work. That is the greatest pathway to success for Harlem School of the Arts.

[O]ne of the greatest acts of social justice that you will ever see: Creating a space and holding a place for people to experience joy and creativity and challenge their thinking.

Some of the ideas that we’ve talked about in terms of social impact and social justice with our work is making sure that we continue to get beyond the walls of HSA to support arts learning for young people in all sorts of environments. We already have in-school programs that partner with local schools to provide high-quality arts education; our teaching artists go into those schools. One of the newer ideas that we’re starting to tease out is what would it look like for HSA to show up in ACS [Administration for Children’s Services] environments, making sure that kids who aren’t necessarily coming to arts centers, arts-based programs, have the opportunity to dance—and dance with world-renowned instructors who are really great teachers and amazing performers?

Our artists are the ones we look to heal, to write the songs, to make the movies, to tell the stories, to write the play, to create visual art, to do the dance. We’re starting to encourage our young people to think: What does the soundtrack of justice look like, and what does the soundtrack or the artwork of justice’s impact look like in your daily practice?

PND: How has the 2020 renovation of HSA’s facilities changed its relationship with the community, funders, and potential funders?

JCH: Our founder, Dorothy Maynor, created the school sort of as a fortress, because if you think about what Harlem was during the late 70s, early 80s, there were some neighborhoods that were literally not safe to go to. This place became a sanctuary for young people in creativity. With the remodeling, the front of the building is all glass windows. Our community can see in and see exactly what is happening. Young people walk by the school all the time and they’re peeking in the windows. You see the little faces pressed against the glass during a concert. It’s just one of the most joyous, most beautiful things. And what it does is say, “Look at what we’re doing.”

The windows aren’t closed; they’re open the majority of the time, which is also an invitation to come inside and be a part of what we’re doing. I think that is the biggest change. Symbolically and architecturally, we went from being still a safe space but a fortress to literally saying to our community: Come be a part of this. And in that same vein, showing the community what we are doing because this is their space. I think being able to literally open it up has meant volumes to how our kids come into the space.

PND: Do you think it’s been just as inspiring to potential funders as it has been to the community and to children?

JCH: I’d like to think so. I’ve been here for six months now, so I’m still very much getting my institutional fundraising legs strong. I think when people see the building, they become that much more curious, because this is a very different architectural piece for this community, so it stands out a little bit more, and it makes people want to say: What is happening in there, and how can I be a part of it and support it? I do think it will attract a different type of funder, a different level of funder.

PND: What would you like non-arts funders to know about arts education?

JCH: I think the biggest thing that I think about in relationship to the arts in general, is that a well-rounded diet consists of protein, carbohydrates, and some sort of leafy vegetable. A well-rounded education consists of math, science, English language arts, history, and the arts. And when you think about the arts, they are the actual application of all of these subjects. It is the actual integration and application of what math sounds like. That’s what music is. Music is what math sounds like. A visual piece of artwork, graphic design, digital music production—that is math in motion.

I would encourage funders to not think of art as something that is exclusive and lives over here as something separate. Art is about the most inclusive human experience that you can imagine, because it brings all of the worlds together—literally all of the worlds—and engages in a dialogue around something as complicated as race, politics, religion. We can do it through art in a safe way and critique art, which relates to those things. It provides us with a commonality, if you will. If people invest in connections, if people invest in the best, highest version of humanity and each other, that is a direct investment in art.

A well-rounded education consists of math, science, English language arts, history, and the arts. And when you think about the arts, they are the actual application of all of these subjects. It is the actual integration and application of what math sounds like. That’s what music is....Art is about the most inclusive human experience that you can imagine.

I would encourage everyone in the philanthropic world to continue to invest in humanity. That’s what art is. That’s what Harlem School of the Arts is. It’s the best, highest, greatest form of humanity, sitting right on the hill in Hamilton Heights in central Harlem.

PND: How did the relationship with the Verizon Foundation develop, and what led to them providing $100,000 in 2022 for technology-based learning? How important are grants like those to HSA’s ability to expand its program offerings to things like podcasting?

JCH: Grants like that are absolutely critical, because one of the things that we also are starting to think more about and be much more intentional about is building pathways for young people to learn skills, to build up those muscles, to start to think about: Where do I fit in in this 21st-century economy that is really becoming skills-based?—and that is really digital. The Verizon Room is a digital design studio in which students are learning 3D animation coding and graphic design.

It’s so important for young people from under-resourced communities to not only have access but to be able to be the author of their own stories and craft their own narratives.

The podcast program is phenomenal, and we do that in collaboration with our Master Artist series because it’s young people who prepare questions, they prepare the interview, they walk through the interview with their teachers and sort of role play.

We want to provide them with the tools to amplify and further broadcast their voices. That is what is so beautiful about technology: It amplifies and broadcasts. We don’t need to just be consumers of content; we need to be creators of content. And the way to do that is not to spend a billion bucks but through the use of the technology that is available to us today.

It’s so important for young people from under-resourced communities to not only have access but to be able to be the author of their own stories and craft their own narratives.

PND: What are your goals for programming and outreach for the next school year? How does fundraising impact those goals?

JCH: Year two is a really super-exciting year because it’s also our 60th anniversary year. It is a foundation-building year for where we want to go for the next 60 years. We want to deepen what we’re already doing through our core disciplines: dance, music, instrumentation and choral, but also digital music production. One of the things we’ve heard people ask for loud and clear is a television studio. We’re looking at trying to implement that and, of course, that depends a lot on funding. Video game design is something that we’ve heard our young people ask for. I think it’s a beautiful mash-up of every single art form coming together. I think of it as interactive film at this point. I’m an avid gamer myself, and I would love to be able to teach kids video games. I'll probably be taking the classes with them.

We’re also thinking about adult education. We realize that adults want to get back out, too, and they want to do stuff. They don’t just want to be talked to; they don’t want to be in lectures. We’re building out a new strand of public programs that will kick off next year. We need support to do all that stuff.

I have found that now more so than ever, places like Harlem School of the Arts are where our community is looking to bring life back into the community, to get back to not necessarily pre-pandemic days, but a pre-pandemic way of engaging and being together again physically and be interesting and try to grapple with some of the challenges in the world.

— Samantha Mercado