Do you have a ‘winning’ narrative?

In the social issue space, new narratives pop up all the time as movements, companies, and organizations attempt to grab and keep the public’s attention. How do you know if (and when) the narrative you’ve created for the social issue you’ve chosen to address is the “winning” one?

While narrative is often conflated with hot-button topics and culture wars, no one “wins” by drowning others out. You win only when the public adopts your narrative as the cultural norm for a given issue—and changes their behaviors to reflect that shift.

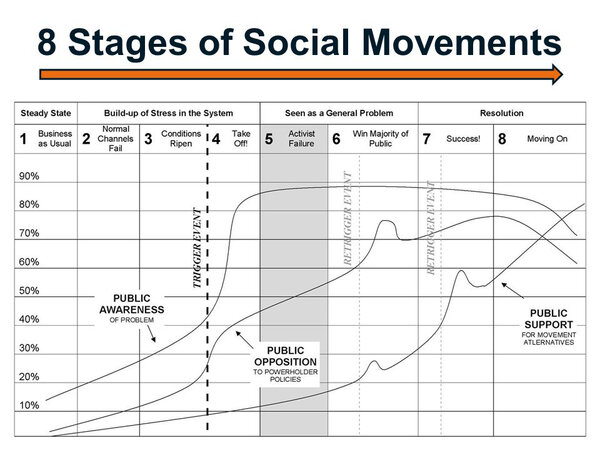

This strategy has been going on for decades, regardless of whether a narrative is built on facts. More than 35 years ago, researcher and movement observer Bill Moyer pointed out that as public awareness rises, every movement has to contend with oppositional narratives and a shift in the effectiveness of their demand platform.

As you can see from this chart, the price of increased awareness is increased opposition and support for alternative narratives. Moyer wasn’t making a judgment call; this series of events is simply what has occurred time and time again.

Regardless of the social issue they’re working to address, today’s leaders must understand that narrative adoption is not a rational undertaking. Whenever the opposing side on an issue raises a challenge, we often see narratives created to change public opinion but in reality do nothing more than exploit facts or events—taking one fact and creating false context to win public sentiment. And though this approach isn’t new, many organizations and movements still seem taken aback when it happens. Again, this is illustrated in Moyer’s stages of movement development.

Below is a guide to knowing whether your narrative has inspired the public to change viewpoints. We look at it in three stages: Narrative Adoption, Narrative Attitude Shifting, and Narrative Behavior Inducing.

1. Narrative Adoption

This stage focuses on a movement’s ability to create a narrative that is understood and adopted by those with moveable (changeable) views. Mistakes often made in this phase include using policy terminology in public adoption strategies and speaking in terms many individuals find unapproachable. The demand platform, or set of desired policies that coincides with narratives for the public, should create a clear understanding of the opportunity for the future and how it will impact the individual. We use various narrative testing methods to understand whether the person can recall a statement, language, position, and attitude of the public to measure narrative adoption by the public—gauging awareness, consumption, and effectiveness of persuasion.

2. Narrative Attitude Shifting

Just because you reach the public and they understand your position from the narrative you present doesn’t mean you’ve succeeded in inspiring attitude and knowledge shifts. This is the confusion we see when movements focus on reach and not on the ability of a narrative to address attitudes, stigma, and bias. We can state what we think, believe, and value—but that doesn’t mean anyone will change deeply held beliefs. Understanding this comes from pre- and post-testing whether deeply held beliefs (known before exposures) are shifting in real time.

3. Narrative Behavior Inducing

Does the narrative actually change one’s behaviors around the issue? This is the core purpose of the narrative and the outcome we most want. The key for long-term adoption that leads to behavior change is whether the narrative allows individuals to feel that the choice is theirs and thus is internalized as an action they do for themselves. Constructing narratives without a full understanding of this need for internalization is a shortsighted approach that will result only in episodic behavior change. This is why we measure consistent behaviors over time and not just once during campaigns.

The next step in assessing your narrative involves where it is focused. Does your movement or organization spend most of its time and resources on a “winning” narrative that’s aimed at people who are already entrenched in a particular position (key stakeholders), ignoring the vast majority in the middle?

We can look at the gun safety narrative as an example. Those on the extreme left are driving current messaging using a strategy of responding to or disproving the right’s most strident narrative: “We must protect the Second Amendment.” By using this narrow strategy, those on the left are assuming that most Americans strongly agree with this far-right narrative.

In reality, most Americans have not adopted a particular narrative around guns; just under 60 percent of registered voters think stricter gun laws are at least somewhat important; moreover, opinions change as time between mass shootings lengthens. As FiveThirtyEight notes, “Public opinion often shifts in favor of stricter gun laws after high-profile mass shootings. However, the spotlight tends to fade over time and shift to other issues, so Americans become less engaged with the issue and support for stricter gun laws reverts to where it once stood.”

Rather than creating a narrative aimed at key stakeholders who are firmly on your side already, spend time and resources developing and sharing a narrative that will educate people who are uninformed about your issue and stance. Don’t fall into the trap of trying to win the argument against the opposition; in doing so, you let them steer the conversation. Your goal isn’t to win the argument. Your goal is to provide the knowledge the uninformed members of the public need to make their own decisions. Narratives that resonate with people who haven’t made up their minds about an issue or candidate can carry you into “winning” territory.

What kind of change are you hoping for with your narrative? Whether it’s already public or still in the creation stage, I encourage you to reexamine your narrative in each of the three stages described above.

Derrick Feldmann (@derrickfeldmann) is the founder of the Millennial Impact Project, lead researcher at Cause & Social Influence, and the author of The Corporate Social Mind. Read more by Derrick.