What Are Your Comparative Advantages?

In our previous article ("Are You an Effective Competitor?", we discussed the reality of competition in the nonprofit sector and defined the four types of resources for which nonprofits compete: customers (i.e., those who are directly served by a nonprofit); funding; human resources: staff, board members, and other volunteers; and publicity or media attention. We also defined the three types of competitors that nonprofits face: direct, substitutable, and indirect.

In this article, we will discuss how to assess your competitors and identify your advantages in comparison with those competitors. And in our third and final article, we’ll discuss how to determine what position you hold in your particular market vis-à-vis your competition (e.g., leader, small player, or one of many fairly strong organizations), as well as the various competitive strategies at your disposal to maintain or improve your position. The ultimate objective of these strategies is to help your nonprofit garner the resources it needs to enhance its effectiveness in achieving its mission.

Your market

To identify your organization’s competitors, you first need to identify your organization's market. Your market is defined by the customers you serve with your programs and the geographic area in which those customers are located. Sometimes the customers you serve are different from the customers you intend to serve — that is, your target customers or target market. We'll discuss that situation, too.

Who are your customers?

Let's start with your customers. How would you describe them? One way to think about it is in terms of the needs your programs are designed to meet; your customers are the people with those needs. What are the characteristics of the people that are important to your programs? Characteristics to consider include age, gender, race/ethnicity, sexual preference, religion, values and beliefs, health status, economic status, education, family status (e.g., whether they have children or not and the age of those children), and leisure-time activities. Next, narrow down the list of those characteristics (and any others that are important to your mission) to those that are most relevant to your programs. The resulting list should be a pretty good description of the customers served by your organization.

Where do you serve your customers?

When you consider the geographic aspect of your market (also called your "service area"), you should think of it in terms of where your programs are offered. That's relatively easy to do if you are a "bricks-and-mortar" type of organization, with a physical location where you provide your programs — for example, a day care center or a health care clinic. Your immediate service area is where your facility is located, and your primary service area is the geographic area where the majority of your customers live. If, on the other hand, you are a center that’s sponsored by an employer, your geographic scope is determined by where your customers work. And if you happen to be a center located in a residential neighborhood, your geographic scope is largely the same as the surrounding neighborhood.

For other nonprofits, the concept of service area is a bit more complex. For example, an environmental group’s programs may be focused on advocacy and/or restoration/preservation work focused on a specific place or habitat. In such a circumstance, your customers — those who volunteer and/or who are members of your organization — may live in or near the place or habitat in question, or they may be spread over a much broader geographic area and simply feel an affiliation with the place or habitat your programs focus on.

Perhaps the most difficult-to-define service area is that of a nonprofit that primarily offers information via a Web site — for example, an online resource center for parents of children with learning disabilities. Such an organization may have a geographic scope that crosses state and even national boundaries and could potentially include the entire world.

All these examples merely highlight the variation in how service area may be defined. The important thing to remember is that your nonprofit's geographic scope does not just encompass its physical location or, in the case of an environmental organization, the specific place or habitat on which your advocacy efforts are focused; it's the geographic area in which your customers are located.

Test your assumptions

If it is difficult for you to describe your organization’s customers and/or geographic scope off the top of your head, you may need to do a bit of research. And even if the above exercise is easy for you and you believe you have a good sense of your market, it doesn't hurt to verify your assumptions. Organizations often have a good sense of who they want to serve and/or the geographic area they think they are serving. But when they do a bit of research to learn more about their actual customers, they frequently discover that the reality — who they are actually serving and/or where these customers live and/or work — is quite different from what they intended — i.e., their "target" market.

To verify your "gut" assumptions, start with your program staff. Typically, they are closest to your customers and should have a good sense of who those customers are and where they live and/or work (depending on which of those is relevant to your programs). Ask them to describe the key characteristics of your customers and the area you serve. Does their description match yours? And does it match the vision you have of the customers you seek to serve — i.e., your target market? If not, you will need to make some adjustments in your assumptions. You may even need to consider adjusting your strategies to help position your organization to be more successful in attracting the customers you seek to serve. (We'll discuss how to formulate and implement competitive strategies in our next article.)

Ask your customers

If you really want to know about your customers, you need to go to the source — your customers themselves. Surveying customers is something the for-profit sector typically considers a necessity — and something all too often overlooked in the nonprofit sector. Unlike the usual approach in the for-profit sector, however, this does not have to be a major undertaking. You can learn a lot simply by surveying a small sample of your customers in person or by phone, or by conducting a small focus group discussion.

A good place to start is with the basic customer information you already capture. For example, most health clinics use intake forms that ask for basic demographic information as well as a customer’s address. A performing arts organization may have a mailing list of those who have requested tickets or pre-season programs by mail. If you publish a print newsletter, your mailing list is a great source of information; by sorting on state, city, and/or zip code, you'll get a good sense of your organization’s geographic service area.

All of these resources can be scanned for information. They also represent opportunities to gather even more information about your customers. If you publish a newsletter, you can insert a short survey in it and provide a pre-stamped envelop for returning completed surveys. If you operate a health clinic, you can ask patients to complete a survey while they wait to see a doctor or nurse. If you're a theater, you can hand out a short survey at the beginning of a performance along with a promotional pen or pencil that audience members can keep as a souvenir of their night on the town.

A simple way to get information about your customers is to identify a small sample of those who have recently used your services and survey them briefly by phone. Ask if they would be willing to tell you how satisfied they were with your services. Most people will be willing to share their thoughts with you, especially if they believe you are genuinely interested in their opinion and want to use the information to improve your programs. And by asking your customers what other organizations like yours they have heard of, as well as their perceptions of those organizations and their programs, you’ll begin to gather basic information about your competitors and how your organization matches up with them.

Another simple research tool is the focus group. Focus groups don't have to be elaborate exercises complete with two-way mirrors, electronic devices to measure subtle reactions, and psychologists observing and interpreting body language. Instead, gather a small group of eight to ten of your customers at your facility and ask them to spend an hour or two with a skilled facilitator discussing your products and services. (While there's a bit more to setting up a focus group than that, our point is that it doesn’t have to be a major and costly undertaking.)

Who competes for your customers?

After you have identified your organization's customers and geographic scope, your next step is to focus on your competitors. Among the three types of competitors, direct competitors are the most significant. These are the organizations that provide the same (or similar) programs to the same types of customers in the same geographic area as your organization. Not only do they compete for the same customers, they compete head-on with you for funding — whether from foundations or from individual donors — and they also compete with you for human resources — potential staff, board members, and other volunteers who want to work for or serve an organization like yours.

To secure your share of these important resources, you need to demonstrate your organization’s value. And to do that, you need to know what your value is — not only to your customers but also compared with your competitors. You need to be able to answer the questions at the forefront of funders’ and donors’ minds: "Why should I give my money to your organization?" And, "What makes your organization a more worthwhile investment than other nonprofits that do the same thing?" You also need to be able to answer the same type of question from potential staff, board members, and volunteers: "Why should I work for your nonprofit?" Or, "What makes your nonprofit better than other nonprofits?" Board members and other volunteers occupy a similar position as your funders — except that they donate their time instead of their money. But as we all know, "time is money" has never been more true than it is today.

In order to answer these kinds of questions, you have to know what makes your organization different. This is what marketers in the for-profit sector often refer to as an organization's "unique value proposition," and what we refer to as your "comparative advantage(s)."

Let's start with your direct competitors. Which organizations serve similar customers in the same geographic area as you do? (Note: If, in your customer research, you found that your organization isn’t serving the customers you intend to serve — i.e., your actual customers are not your target customers — then in identifying direct competitors consider organizations that serve your target customers.) List these organizations off the top of your head. Usually, nonprofit leaders have a good sense of who their direct competitors are. The leaders of those organizations are the people you tend to run into at community meetings, and the organizations themselves tend to submit proposals to the same funders you do.

Again, as you did when you described your own customers, be sure to test your assumptions. First identify those people whom you consider to be the strategic thinkers in your organization. This group should include staff, volunteers, and/or board members who regularly read papers that focus on your service area, who network with other professionals and community leaders, and/or who attend meetings and conferences focused on issues of importance to your organization.

Ask these key "informants" which organizations they consider to be your direct competitors. While the list will be primarily comprised of other nonprofits — those that compete with you not only for customers, but for funding as well as human resources — consider both government and business-sector competitors, as they also compete for your customers and some of the same human resources. Next, ask your informants to rank their lists and to provide a short sentence or two about why they ranked a competitor as they did.

One way to quickly develop such a list is to conduct a brainstorming session at a staff and/or board meeting. Ask participants to think about the question in advance and to do some basic research (e.g., an Internet search, an informal phone survey of their colleagues, etc.). Then, compare the list developed in the meeting with those developed in sessions with your key informants and consolidate the responses into a single list. Rank the competitors on the consolidated list, making absolutely sure you are clear about your top three to five competitors.

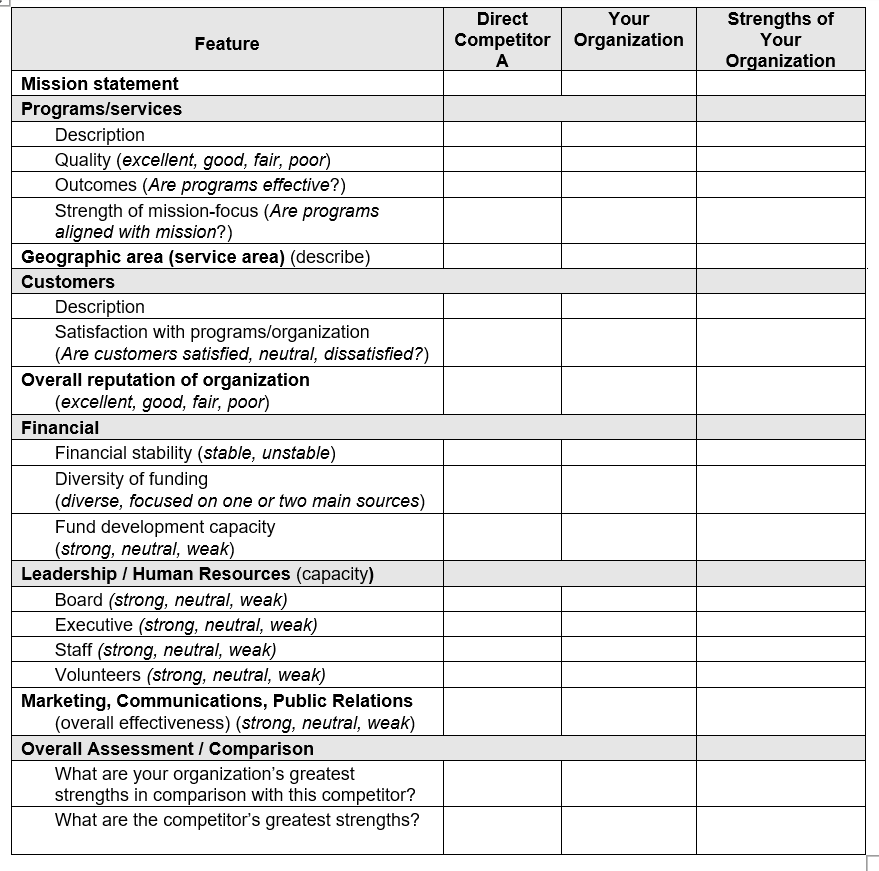

Next, create a table like the one shown below. This exercise will help you gain a better sense of your organization and how it compares with your competitors, especially with respect to the four resources you need to achieve your mission: customers, funding, human resources, and media attention/publicity.

Complete the table first, drawing on your current knowledge and understanding of your organization and its competitors. As mentioned above, if you have conducted basic research on your customers (e.g., surveys, interviews, focus groups), use that information to help you complete the table.

Even if you believe you can complete the table from your own knowledge, you need to make sure you do so objectively — not the easiest thing to do when it comes to assessing the competitive position of your own organization. To avoid the "I know what I need to know" trap, get additional input by reviewing your competitors' Web sites. These days, most organizations have Web sites, making this type of research fairly easy to conduct. If a competitor doesn't have a Web site, or provides only minimal information on its site, try to get your hands on its marketing materials (i.e., brochures, newsletters, etc.). In addition, you should audit, on an ongoing basic, your local newspaper and journals in your field for news about your competitors. What kind of publicity are they receiving? What trends may impact your customers and their need for and use of your services? Your board members, staff, and volunteers also can be great sources of information about your competitors (this information is what marketers refer to as "competitor intelligence"). Enlist them as much as possible in your effort to learn more about your competitors. One way to do this is to bring them together in a meeting to review and comment on the comparison tables you created (see above). This can be a fun exercise and helps make everyone more aware of the external environment in which your organization operates. And with that better understanding, your human resources will be better able to help market your organization.

Substitutable competitors

Now do the same exercise for your substitutable competitors. Generally, substitutable competitors compete most directly for your customers, rather than for other resources — that is, they meet the same needs your organization does, but in different ways.

For some organizations, substitutable competitors are obvious; for others, they're more difficult to identify. If you are a day care center, your direct competitors are other day care centers. Your substitutable competitors are the many ways that working parents meet their childcare needs, including nannies, grandparents, and themselves. If you are a theater offering live performances of contemporary plays, your direct competitors are other theaters serving customers in the same geographic area. Your substitutable competitors are the many ways that people fill their cultural needs, including movies, in-home DVDs, book readings/signings, and so on. If your organization offers after-school tutoring for elementary school students, your direct competitors may be private tutors, as well as organizations such as SCORE and Kaplan. Your substitutable competitors include sports programs, lessons of various kinds, and youth programs such as Girl/Boy Scouts.

Identify your top three to five substitutable competitors and determine your organization’s strengths relative to them. Depending on whether a competitor is a specific organization or more generic, such as a different way that customers might fill a need (e.g., in-home DVDs vs. live performances), you'll have more or fewer features to compare. If your substitutable competitors are other organizations, you might want to complete the same kind of comparison chart as you did for your direct competitors (see above). If a substitutable competitor is more generic, make a simple comparison that focuses primarily on outcomes — that is, on how that competitor meets its customers’ needs, as compared with how your organization meets those needs.

A good exercise for organizations that have less tangible substitutable competitors is to consider the features of their programs/services, as well as the benefits that these features create for customers. Take, for example, the community-based theater and in-home DVDs. Both meet a need for entertainment. Delving beneath the surface, however, the community-based theater may identify the fact that it offers live performances as a key feature of its programs/services. The benefit to its customers is the sense of community fostered by its performances and the opportunity to see local talent — something unavailable outside the theater's service area. Its customers may also be drawn by the desire to experience something more "cutting edge" than the DVD version of a big-screen feature that’s already months old. Conversely, among the drawbacks of live theater are its cost, the difficulty of finding convenient parking, and the limited number of performances offered — all of which contribute to making live theater less accessible to potential customers.

In general, the comparison between your organization and its substitutable competitors is less of an "apples to apples" comparison than that for your direct competitors. Even if the substitutable competitor is providing the same type of service — for example, a nanny who provides childcare as a substitute for a day care center — the comparison is more about different features and the benefits of those features. A feature of a day care center is that it serves many children. A benefit is that it offers greater opportunity for socialization than does a nanny and typically costs less than a nanny does.

The comparison of your organization's features and benefits to those of your substitutable competitors allows you to identify more specifically who your target customers are. As you think through why a customer would choose your programs/services over those of your substitutable competitors, you will clarify the aspects of your programs/services that are most important to your customers.

What are your comparative advantages?

With these exercises under your belt, you should have a good sense of your organization’s strengths and are ready to identify your key comparative advantage(s) — the foundation of your competitive strategy. Review the various advantages you identified as you compared your organization with each of your competitors, direct as well as substitutable. Which advantages appeared most frequently? Which ones are most significant from the point of view of the three main resources you are seeking to attract, particularly in the eyes of your target customers? Next, narrow the list down to three most important advantages. Then, see if you can develop a statement that summarizes those three comparative advantages into a single advantage that your organization has in its market. In the for-profit sector, this is often called your unique selling or value proposition, and it’s directly related to your organization’s branding — what some aptly describe as your organization’s "promise" to its customers.

For example, the unique value proposition of the neighborhood day care center may be the fact that it brings together all the young children in the immediate neighborhood and creates a real sense of community and personal caring for and among the families it serves. The unique value proposition of the community-based theater featuring live performances may be that it encourages community members to come together to view contemporary plays and then hosts post-performance discussions of the issues presented, while serving as a supportive training ground for aspiring local artists.

How well do you communicate your value?

It is this message about your organization’s unique value proposition — its primary comparative advantage — that you need to communicate often and effectively in order to gain visibility in your market and attract the resources you need to successfully achieve your mission. So, ask yourself: How well does your organization communicate this message? You should have a sense of this from the direct competitor comparisons you did. To gain further perspective on this vitally important question, however, you need to consider your indirect competitors.

Indirect Competitors

While your direct and substitutable competitors compete for your target customers, indirect competitors compete for other resources. These are the organizations in your service area that everyone knows about. They're the ones that come immediately to mind when people are asked to name the leading nonprofit organizations in your community. They're the organizations that are most "visible" to the community — they get the lion’s share of the media attention, attract the most influential community members/leaders to their boards, and are able to secure a steady stream of funding from community-oriented philanthropists.

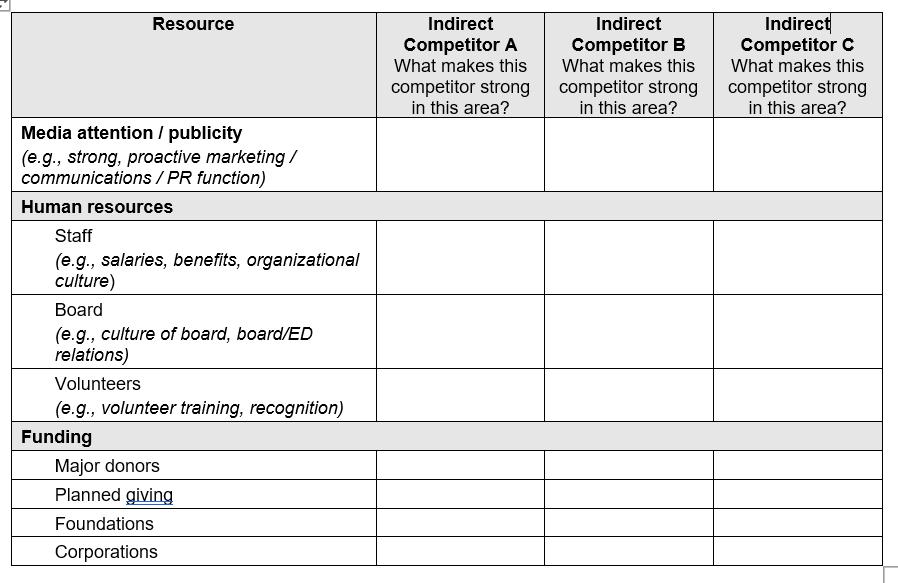

As you did for your direct and substitutable competitors, make a list of the top indirect competitors in your service area. Next, ask for input from your staff, board, and other volunteers, paying particular attention to what makes these organizations strong. What makes them able to attract these resources when so many other nonprofits struggle to do so? What can you learn from them?

Chances are that these organizations are able to communicate their unique value proposition in a way that clearly demonstrates to all stakeholders the importance of their work and how they effectively meet the needs of their customers. Complete the following table for the top three indirect competitors in your service area. Then share the results with your board and staff members and solicit their input.

In order to learn from your indirect competitors, consider their comparative advantages — the strengths that enable them to attract resources. Review the list you developed and think about whether your organization has the same advantages (and whether you need to do a better job of communicating them), or whether you need to develop these strengths on order to compete more effectively.

Conclusion

By now, you should have a good understanding of how your nonprofit compares to others in your market and community. You should also have developed a good sense of your comparative advantages. In our third and concluding article, we’ll discuss how to bring all this information together to assess your current position in the market vis-à-vis your competitors, as well as how to define your desired position. And we'll also discuss how you can use this information to develop and implement strategies for attaining and maintaining your desired position.

In the meantime, do your homework: identify your competition and determine how your nonprofit compares. Be ready to develop your strategy for achieving and maintaining your desired market position. And, remember, it's not about "beating the competition," but rather about playing to your organization's strengths in order to "win" on behalf of your mission.

David La Piana and Michaela Hayes are the authors of Play to Win: The Nonprofit Guide to Competitive Strategy (Jossey-Bass Publishers, 2005).